Radio: live transmission

You may have noticed in recent months that a few JC newsletters have been breaking out into audio format. I’m on Spotify. I won’t deny this has been a personal ambition for a while now. With Substack, it is surprisingly easy to go nationwide.

My personal preference for “discretionary content” these days — how I read for pleasure, that is — is audio: like everyone I spend all the time at work reading, usually off a screen, my eyes are going bung, so for pleasure I would much rather listen to audiobooks, and podcasts and find it increasingly exasperating when authors do not publish recorded versions of their material.

By the way: if you find a narrator as good as Martin Jarvis (e.g., Oliver Twist), Wanda McCaddon (e.g., The Guns of August), or David Horovitch (e.g., The Good Soldier Svejk), the dusty old classics come to life.

I suppose it is a sign of our attention-depleted times that sitting down quietly to read a text is impossible with all the distractions. In my case, it tends to send me to sleep.

Also, audio is the most economical way of consuming literature. No doubt this comes at great cost to budding authors, but Audible’s policy of selling any book on its site for one £6 credit is a pretty hard value to pass up.

So, I started recording a few JC newsletters.

I find it is a useful discipline, reading a newsletter out: you quickly work out what works, what doesn’t, and when your logic doesn’t flow — which is quite often, in my case.

I have some decent recording kit, too, so there is scope for a bit of fun with mixing and so on, though it is still quite the time-sink if, as I had suspected, no one is going to be listening to me drone on in my nasal mid-Pacific accent.

So imagine my surprise when recently a reader told me not only did he listen to the recorded versions, but he put it on his car and his wife had to listen to it too!

“I also quite like the podcast format and often listen to them when I am driving (sometimes against the wishes of my wife, who is my usual passenger)”

I am so sorry — all I can say is, you poor thing!

Aside from inflicting my droning on your spouses, loved ones and pets, I thought I should ask — does anyone else prefer the podcast format?

If so, I will lean into it a bit more. I have a vague plan to do some more free-form sessions about the key clauses of the ISDA — not so much read-outs but discussions around the points in premium articles — but if this is how folks best enjoy content, I will change my approach. Do let me know, either in the comments or by DM or whatever.

Fictitious cases, AI, negotiable cows and access to justice

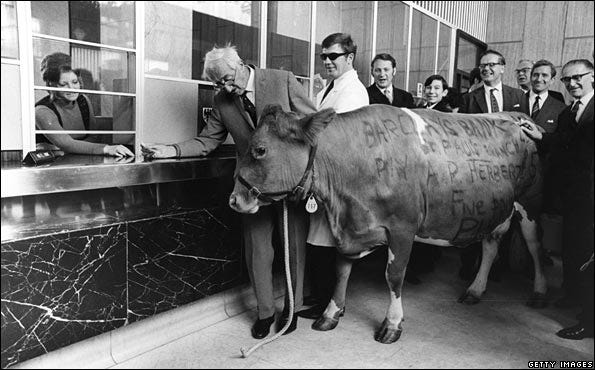

“Was the cow crossed?”

“No, your worship, it was an open cow.”

These and similar passages provoked laughter at Bow Street to-day when the Negotiable Cow case was concluded.

—Board of Inland Revenue v Haddock (1932)

In Messing v. Bank of America N.A., 792 A.2d 312, a case about presentation of a bank check in 2002, the seven-seat Court of Appeals in Maryland acknowledged the celebrated English case of Board of Inland Revenue v Haddock (1935):

In that case, the protagonist, Mr. Haddock, after some dispute involving uncollected income-taxes owed, elected to test the limits of the law of checks as it existed at British common law at the time. Operating on the proposition that a check was only an order to a bank to pay money to the person in possession of the check or a person named on the check, and observing that there was nothing in statute or custom at the time specifying that a check must be written on paper of certain dimensions, or even paper at all, Haddock elected to tender payment to the tax collector by a check written on the back of a cow.

When Mr. Haddock was then arrested in Trafalgar Square for causing an obstruction, and summoned by the revenue for non-payment of income tax, Mr. Haddock said it was “a nice thing if in the heart of the commercial capital of the world a man could not convey a negotiable instrument down the street without being arrested,” and instituted procedings against the metropolitan constabulary for false imprisonment.

So the court held:

It cannot be unlawful to conduct a cow through the London streets. The horse, at present time a much less useful animal, constantly appears in those streets without protest, and the motor-car, more unnatural and unattractive still, is more numerous than either animal. Much less can the cow be recorded as an improper or unlawful companion when it is invested (as I have shown) with all the dignity of a bill of exchange.

Board of Inland Revenue v Haddock is, of course, fictitious: it was written by the great humorist A.P. Herbert for Punch magazine. You can now find it in collections such as Uncommon Law: 66 Misleading Cases, a volume which every student of the law should have on her shelf.

In any case, judicial recognition of disputes that illuminate the fundamental essence of things, even if they are imaginary, is hardly new. It scarcely matters whether the Court knows they are imaginary — the Court in the Messing case was careful to state that it did — it is surely the underlying legal principle that is important: a merchant should be able to bear a negotiable instrument in the city of London without undue harassment.

And so we come to the recent news that a legal firm has been caught out in its submissions for judicial review of a local authority’s decision — JC’s own local authority the London Borough of Haringey, as it happens — not to grant accommodation to a homeless applicant.

In a fulsome and legally correct submission, the applicant’s counsel cited a number of judgments by way of precedent, all of which were made up.

Now: this was not malicious but, most likely, a “hallucination” by a large language model, which the lawyer used to assist in her research. The lawyer used ChatGPT, or something like it. (The barrister has not formally admitted this, and seems to have dissembled about it when challenged in Court, but it seems pretty obvious this is what went on.)

However, the finding which I can make and do make is that Ms Forey put a completely fake case in her submissions. That much was admitted. It is such a professional shame. The submission was a good one. The medical evidence was strong. The ground was potentially good. Why put a fake case in?1

The response from the profession here has been predictable and reactionary: the lawyer has been roundly castigated, and the case taken to sound a warning as to the dangers of artificial intelligence. There have been many thought pieces along these lines, along with some fairly unsparing public criticism by the judge in the case.

Commentators are as disapproving as they are baffled: why invent these cases when, in fact, they were advanced to support arguments that were in any case correct, and could be found in genuine authorities?

There’s a simple answer to this: researching by LLM is pretty good, is getting better, and it is a lot quicker than manual research of databases to which a young lawyer might not have access in any case.

In a profession costed and billed on a time-and-attendance basis, AI is not just a smart choice: if you want research, it is the only choice for a customer on a budget, as presumably a homeless man being represented by a pro bono law centre would have been.

It is a good choice, in fact, for any customer on any budget. It is not like, these days, a buyer of legal services has any choice: if you believe Magic Circle firms do not use LLMs to support every part of their operation every day, I have a bridge to sell you.

To say, as some learned commentators have, that “AI should not be used for such serious legal research—that is, the legal research on which others will rely”2 is absurdly Luddite: about as sensible as warning a lawyer off Google.

If the proposed alternative is to trawl through online data sources, case reporting services and law reports and texts, do not expect that the case of a homeless man represented by a pro-bono community law centre will be researched at all.

The answer is, as with any research tool, to use it with care, experience and in conjunction with other sources.

Part of the problem is the poor public access to decided cases. Given that decided cases form part of the common law — they are a primary source for the law we are all deemed to know — ignorantia juris non excusat — it is a matter of some scandal that those cases are not all available, in full, in a catalogued database. Fewer than half of all reported decisions make it onto the free British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII) website:

There is a restriction on the number of English cases from Divisions of the High Court which can be added to the BAILII database which arises from the fact that the shorthand-writers who transcribe judgments which have been given verbally (as opposed to judgments handed down on paper) may own the copyright in the transcribed version of the judgment. Copies of judgments in published law reports may also be subject to copyright. This prevents the judgment being added to the BAILII database without the consent of the shorthand-writer or law report publisher. BAILII, being a free web site, has no funds with which to acquire a licence to copy and display the transcripts. BAILII continues to press for the system to be changed so that all judgments may be freely available.3

This makes it hard for a busy young lawyer to check case references. The law of the land should not be under copyright. That it is, and that the profession is not more bothered about it than it seems to be, is something we should be agitating about.

No injustice was done. The court was not, substantively, misled.

LLMs are a fact of life. We should be more constructive about working out how they can be put to use, bringing research and legal analysis to people who have, historically, not had it. The legal teams have been caught out here, but the profession’s reaction — disciplinary procedure — seems counterproductive. That the case involves those representing a homeless man on legal aid makes the profession’s reaction all the more regrettable.

Lucy Letby

My fascination with the legal and systems issues thrown up by this case continues. Nothing quite ready to push publish on yet, but here are some of the issues:

Intent, motive and motivation: it is trite law that you do not need a prove a motive to convict for murder, but where the evidence that there has been a murder in the first place is ambivalent, doesn’t the lack of any motive, motivation, or even a pre-identified disposition to similar murderous acts weigh quite heavily against the prosecution?

Was it legalese wot did it? I have access to transcripts of key legal submissions in the case: in particular, defence applications for further disclosure of how charges were selected, seeking orders that the evidence of the prosecution’s lead witness be excluded (or that he be declared hostile) and the Defence’s final submissions to the jury. One thing that strikes me is that the barristerial language — and length — in which these submissions were rendered might have made it all a bit hard to follow, even for the judge.

Conspiracy theories: Is anyone making up conspiracy theories? If so, who? And what is a conspiracy theory anyway, and how do you tell them apart from real theories?

Eyes peeled on the Jolly Contrarian Crime and Punishment channel for that one.

Law Commission consultation: criminal appeals

For anyone generally interested in the criminal justice procedure — how could you not be, as a lawyer, after the Post Office Horizon scandal and the LIBOR appeals? — The Law Commission is engaged in a wide-ranging consultation on the criminal appeals procedure, including the Criminal Cases Review Commission and, I suspect, expert evidence (even though it has published and been ignored on that subject in the last decade).

They have made it very easy to engage with the consultation at whatever level of detail you would like to.

Here is where you can do that.

Go well!

Ayinde v LB Haringey 2025 EWHC 1040, page 12.

https://www.bailii.org/bailii/faq.html

Share this post